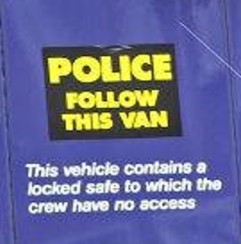

A sign on the back of a security van: “This vehicle contains a locked safe to which the crew have no access.” Imagine if the school curriculum came with a similar tamper-proof warning: “THE CURRICULUM IN THIS SCHOOL IS CONTAINED IN A LOCKED SAFE TO WHICH TEACHERS, SLT AND GOVERNMENT HAVE NO ACCESS.”

As it stands, the curriculum in any given subject in any given school can be a moveable feast, disrupted one year by national reforms, the next year by the preferences of a new Head of Department, the next year by the decision to switch exam boards, the next year by a reduction in the number of hours allocated to each subject. This leads to teachers constantly teaching new topics for the first time and relying on piecemeal resources lifted from the internet.

A few examples from the history department where I started my career:

- We spent one half term of Y7 history making paper mache castles. It might have been fun, but it wasn’t history.

- The holocaust and the atomic bomb were taught in the summer term of year 9 but this was often interrupted by activities week, sports day and trips, so these crucial topics were barely touched.

- The GCSE course comprised mostly of topics perceived to be more accessible to our pupils, such as the American West and Medicine Through time, with coursework on Jack the Ripper. Did this prepare students for history at university? Did it fulfil their democratic right to leave school with a basic understanding of the world around them?

- The curriculum taught in each classroom would depend on the preferences of the teacher; we would sometimes deviate from the curriculum to teach an area of personal interest e.g. the Olympic Games or London through time (might be a good thing in the right hands but it’s a lot to ask from inexperienced teachers or teachers teaching out of their subject).

It was a curriculum guided not by powerful knowledge, eternal truths and threshold concepts but by the whims of teachers and the state of the department filing cabinet on any given day. Despite the fact that this particular history department had been in place for decades, we had failed to establish a secure curriculum and a stable set of teaching materials to go with it. The classroom experience suffered as a result, particularly for pupils taught by supply teachers and non-specialists.

We can’t guarantee every child an exceptional teacher, but we can guarantee every child an exceptional curriculum.

Our national tamper-proof curriculum would be an entitlement for all pupils. In each subject the content would be laid out in a logical sequence: year by year, term by term (the current National Curriculum simply sets out what pupils should be taught in each key stage). The stability of this curriculum would enable resources to latch on to it: lesson plans, topic tests, low-stakes quizzes, knowledge organisers and masterclass videos by subject experts.

With the whole country studying the same stuff, publishers would be able to produce textbooks cost-effectively. Perhaps most excitingly, we could collate and share the best work produced by students across the land. Forget arbitrary levels and age-related grades – pupils could see how their work compares to some of the best work in the country.

There’s one massive problem with the idea of a ‘locked-up’ curriculum though – the curriculum should not be hidden away, it should take centre stage in our schools and in our society. Safe in the knowledge that it won’t be tinkered with, it could be emblazoned on walls, plastered on corridors, published on the website alongside resources that pupils and parents can access at home. Over time the curriculum could become a sacred national treasure, enshrined in our national psyche. Let’s have a national holiday on the rare occasion (every ten years?) that we update it!

The benefits for teachers’ workload would be immense. Earlier this year I walked through the staff room of an independent school. Teachers were reading newspapers and academic journals; they huddled in subject groups planning and reviewing lesson materials. They did this because the curriculum itself had been stable for years, allowing expertise and resources to gather around it.

Does this impede the autonomy of teachers? Of course not. Delivering the curriculum – linking it to prior knowledge, deftly checking for understanding and providing precise feedback– is the very essence of teaching. Deciding what to teach places a huge burden on individual teachers. In every profession there are accepted standards that professionals simply don’t interfere with, whatever their personal preferences.

It’s time to stop tweaking, tinkering, chopping and changing. The curriculum – the stuff kids study so that they leave school with an understanding of the world around them – is too important to be left to chance.