This is the second in a 3-part series of posts reflecting on my recent visit to Dixons Trinity Academy in Bradford. The first post described the power of over-communicating simple, clear messages. This post explores the culture of the school in more detail.

When describing a great school culture there are a couple of clichés that I’m keen to avoid: that it ‘runs through the school like the letters in a stick of rock’; that it’s ‘woven into the very fabric of the school’. Yet at Dixons Trinity the culture is so intrinsic to the school that it would be difficult to say where the letters end and the rock begins, or to spot the cultural thread amidst the fabric that surrounds it.

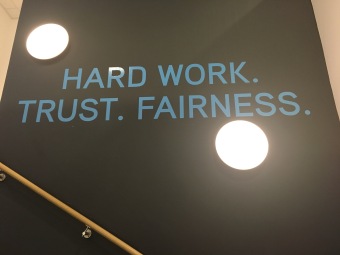

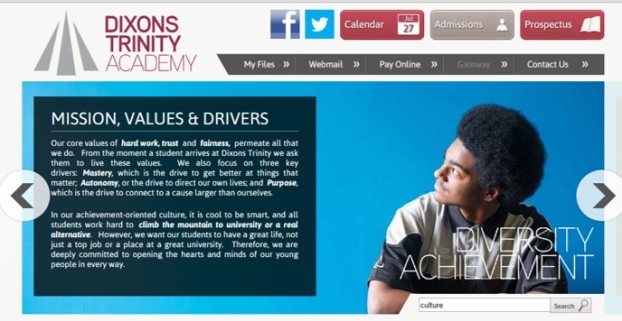

The core values of the school are hard work, trust and fairness. “These are the root of everything we do” explains Principal Luke Sparkes. These values are supported by three motivational drivers: autonomy, mastery and purpose. These drivers will be familiar to readers of ‘Drive’ by Daniel Pink, a wonderful book about human motivation which can be summarised by the by the idea that once you pay your kids to take out the trash, they’re unlikely to do it again for free. Instead of extrinsic rewards such as cash, merits and vivo miles, Daniel Pink and Dixons Trinity focus on intrinsic motivation – a point captured on the wall of a science lab – “we do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do”.

“We don’t rewards kids here” says Luke – “the reward is that one day these kids will have a great life”. This doesn’t lead to a cold atmosphere – the students that I spoke to beamed with joy as they described their school – and Luke added that they provide occasional treats such as the ice cream van that recently awaited Year 10 students as they filed out of an exam.

It’s not surprising that a fresh-start school like Dixons Trinity has established a rich culture, but I think there’s a couple of points that all schools can learn from them. Firstly, the stability – the sense of permanence – of its culture. This continuity of culture is typified by the wall display. In ‘the heart’ – an open space at the centre of the school – one wall is covered with the words “home to the hardest working young people in Bradford.” The purple wall of a corridor is emblazoned with yellow block capitals which deliver the Springsteen-esque line: “WHEN ONE OF US SUCCEEDS WE ALL SUCCEED”.

The student contract for each cohort – signed by every child when they arrived at the school – is mounted on the wall of the lecture theatre, providing a daily reminder of each child’s commitment to their own learning. I like the permanence and confidence that this conveys – a school so sure of its ethos and values that it paints them to the wall; a school so clear in what it requires of its students that it asks them to sign their commitment to a set of ‘contractual obligations’ and then reminds them of this commitment every day for the next 5 years.

This culture is enacted each day, made real by routines, rituals and shared stories. Students develop autonomy, for example, by choosing their own ‘stretch projects’ which they work on outside of lessons over several weeks before presenting – without notes – the fruits of their labour to their peers. `

Caring about culture is not a new thing. The Ofsted handbook includes more than ten references to ‘culture’, and in the ‘outstanding’ section for Leadership and Management the opening criterion is “Leaders and governors have created a culture that enables pupils and staff to excel”. Yet I wonder if we’ve shown enough curiosity about how to build this culture, particularly in communities where the school needs to proactively assert its own values, rather than allowing the values of the community to waft over the school gates.

At Dixons Trinity the culture they have grown is a living, breathing thing, articulated with the same clarity by students in Year 7 as the founding principal. It’s the clarity, stability and daily reinforcement of this culture through artefacts, routines, signs and habits that was so striking about Dixons. There’s a school of thought that if you get teaching and learning right, everything will follow, but here it’s the other way round, with a rich culture enabling great teaching by ensuring students’ commitment to their side of the bargain. In my final post about Dixons, I’ll explore how this culture liberates teachers to teach great lessons.